According to a 2021 Pew survey, 72% of Hindus say that “eating beef” disqualifies a person from being a Hindu. Only 49% said “not believing in God” was a disqualifying factor.

Since ancient times, Hindu scriptures have discouraged killing cattle, including both cows and bulls/oxen. In modern times, the Constitution of India (Article 48) encourages States to take steps to prohibit the slaughter of cattle, and 20 out of 28 Indian states have accordingly made it illegal to do so. The only states where cattle slaughter and beef eating are legal are those that have large non-Hindu populations.

Vegetarianism and the Importance of Dairy

India has the world’s largest vegetarian population. Milk and milk products are a crucial source of protein and calcium in a vegetarian diet. Even more importantly, access to milk can be the difference between life and death when the crops fail or during times of food scarcity.

Perhaps because of this, Hindu scriptures discourage the commercialization1 of dairy products, considering it unethical to put a price on something so vital to life. On the other hand, giving away milk and milk products is considered meritorious, while gifting a cow (godaan) is considered the most meritorious of all deeds one can perform.

The Mahābhārata, for instance, says, “There is no gift equal to the gift of a cow. It rescues from all sins, even the sin of brahmahatyā (killing a Brahmin)2.”

As a result, most Hindu households traditionally kept cows at home for the family’s dairy requirements. The animals are not just a part of the family; cows, especially, are considered to be like mothers because they nourish through their milk.

This is one of the reasons most Hindus recoil at the idea of harming cows, leave alone killing or eating them.

The Hindu veneration of cows and cattle, however, goes beyond the importance of dairy for vegetarians. It is, in fact, a multifaceted relationship going back to prehistoric times, spanning territory and wealth, national identity, religion, and politics.

India’s Origin Story – A Prehistoric Battle Over Cattle

The Rigveda (pre 1500 BCE ancient Hindu scripture) contains several hymns that describe a furious battle called the Battle of the Ten Kings fought on the banks of River Yamunā and River Rāvi, which flow through modern India’s Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, and Punjab. Historians agree that this battle was an actual historical event.

As per these hymns, a confederation of 10+ clans ganged up and attacked the Bhārata clan in a bid to seize their cattle, but after prolonged fighting, the Bhāratas were successful in defeating their opponents and recovering their own cattle as well as capturing that of their opponents.

The Bhāratas went on to drive their opponents out of their lands, westward, and expand their territory in the Indian subcontinent, eventually becoming a powerful superstate, winning the loyalty of and receiving taxes from all the surrounding kingdoms in return for protection.

We don’t know the exact geographical extent of the ancient Bhārata empire, but we do know that their legacy has extended and endured far beyond their empire. For instance, the Vishnu Purāna (a 1st millennium B.C. work) says:

उत्तरं यत्समुद्रस्य हिमाद्रेश्चैव दक्षिणम् ।

वर्षं तद् भारतं नाम भारती यत्र संततिः ।।

Translation:

“That which is north of the ocean and south of the highest Himalayan peaks

Is the land called Bhārata, where dwell the Bhārati”

To Indians, India has always been “Bhārat” for as long as we can remember. And it may all have begun with a battle for cattle.

The Vastness of India’s Cattle Wealth

We are not talking, here, about a few heads of cattle, but about vast herds, probably numbering in the millions.

The Indo-Gangetic Plain has a native geography similar to the African savanna. In the ancient times, this area had vast open grasslands with wild cattle for the taking and semi-nomadic tribes establishing their territories through massive cattle raids. Cattle was the main form of wealth, and tribes with large herds of cattle dominated prime pastures, controlling land and water resources.

In Valmiki’s Rāmāyana, for instance, Prince Rama of Ayodhya is exiled for 14 years. Before going away to live in the forests, Rama gives away all his wealth, which includes (among other things), milch cows, female calves, bulls for carrying load, and oxen for ploughing fields to a number of people in units of “thousands” (see Rāmāyana 2.32).

Similarly, the Mahābhārata has verses describing Yudhishthira and other kings giving away cows in units of “thousands” or “hundreds of thousands” as charity, while the Bhāgavata Purāna mentions Krishna’s foster father, Nanda Mahārāja (the chief of a large cow-herding community in Vrindavan), as donating “two million” cows to celebrate Krishna’s birth.

Some scholars think that these numbers may be exaggerations or figures of speech, but there is good reason to believe that they may be closer to the truth than assumed.

As of August 2025, according to the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service report, India has 307.5 million heads of cattle – the world’s largest cattle population, and accounting for 20% of all cattle worldwide. For comparison, Brazil has the second largest cattle population, at 238.6 million, while the U.S. and China had 88.8 million and 73.6 million heads, respectively, as of 2024.

Mahābhārata – the Saga of the Bharata Clan Retold as a Religious Epic

The introduction to the Mahābhārata says that its composer, Sage Vyāsa, having studied all the Vedas and other associated works, wanted to summarize the contents therein for the benefit and edification of the common man. The result of his endeavors was an epic poem about 15 times the length of the Bible.

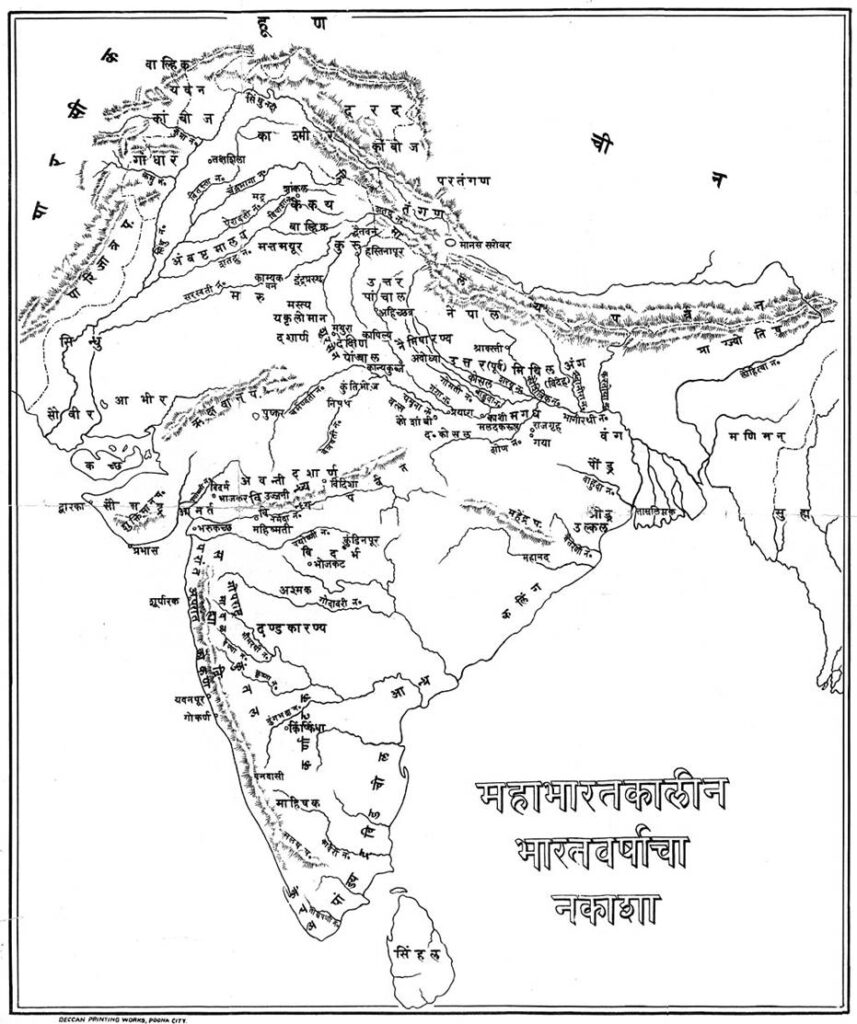

The Mahābhārata is told primarily as the saga of the Bhārata clan, beginning with its founder, King Bharat, whose descendants are called Bhārata. In this sense, it is based on the historical event of the Battle of the Ten Kings. A short summary of the story is that decades of strife and bickering among cousins culminate in a great war to preserve dharma (righteousness), and despite having a much smaller army, the righteous side wins, and dharma prevails.

Essentially, the Mahābhārata is an epic work of religious literature illustrating the theory of karma (actions and their consequences) using numerous historical stories found in the Vedas, weaving them together to create an intergenerational epic spread across a vast geographical canvass. In other words, moral instruction through example is the main aim, with historical stories playing the supporting role.

The central figure in the Mahābhārata is Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu, who is the God of sustenance and preservation in Hinduism. Vishnu, it is said, takes birth in the mortal world to restore dharma whenever the world becomes riddled with corruption and immorality.

While the Mahābhārata itself focuses on the battle between dharma (morality) and adharma (immorality), the appendix to the Mahābhārata contains the story of Krishna, his earthly lineage, birth, childhood, and early youth (see Harivamsa).

It is no coincidence that Krishna is described as having been raised in a clan of cowherds (Yādavas) in the Indo-Gangetic heartland. The Harivamsa describes Krishna’s birth and childhood as a young cowherd boy in great and delightful detail. Some of his nicknames arising from this aspect of his life are Gopāla (raiser of cows) and Govinda (protector of cows).

God as a Cowherd

During the 1st millennium CE, there emerged a religious movement in India called the Bhakti movement. Before that, religion in India had strong ritualistic and intellectual components, both of which were the domain of the Brahmins. The general populace had access to the Gods or to the scriptures only through the Brahmins.

The Bhakti movement (bhakti means “devotion”), however, preached that love and sincere devotion were the best paths to God, effectively sidelining both the ritualistic and intellectual aspects of religion. This movement, which swept the length and breadth of India over the course of a thousand years (roughly 7th-17th centuries CE), greatly democratized religion, giving the masses direct access to God.

Bhakti literature, which was deliberately designed to inspire adoration of God, focused on stories that made God relatable and adorable. Krishna as a child, growing up in a village of cowherds (Gokul), herding and protecting cows, playing the flute (typical of cowherds/shepherds in the ancient world), and being the object of adoration of all who laid eyes on him, is one of the most popular and enduring themes of Bhakti literature.

Ancient cow-herding and dairy-farming themes, therefore, became an integral part of the religious consciousness of the vast majority of Hindus through Krishna’s childhood as portrayed in Bhakti literature. Images of Krishna are often portrayed with cows in the background.

Cow Veneration and Hindu Nationalism

Hindu veneration of cows evolved organically over the course of millennia, but has taken on a more aggressive aspect in recent centuries in the face of external threats.

Medieval Islamic invaders used cow slaughter as a symbolic act to humiliate Hindus and break their spirit as part of their conquest strategy. Over the centuries, forced conversions to Islam included instances of compelling Hindus to consume beef to confirm renunciation of their faith.

In contemporary India, cow slaughter during Eid al-Adha remains a sensitive issue, sometimes leading to communal tensions when conducted publicly or illegally.

All this has contributed, over the past few centuries, to Hindus developing the idea that eating beef disqualifies a person from being Hindu even though there is limited scriptural basis for a blanket disqualification.

Of course, killing cows or eating beef has always been discouraged by the scriptures since ancient times, but the scriptures do not say anything about it leading to excommunication from the religion. Some scriptures primarily indicate that those responsible for performing certain religious rituals were required to maintain ritual purity, including by not eating beef.

However, faced with the threat of religious erasure, Hindus have adopted a more aggressive religious posture themselves, and cow reverence beyond early historical norms has become an integral part of the modern Hindu identity.

Cattle Reverence Around the World

The Hindu veneration of cows is not eccentric. Most ancient people understood the great importance of cattle to human populations, but modern urban lifestyles have made us forget why cattle are worthy of veneration.

Pastoral and agrarian societies attached great economic importance to cattle. Cattle provided milk, dung, blood, meat, hides, and transport to herding communities, and also served as draft animals in agriculture. In many of these societies, a person’s wealth was measured by the size of their herd.

In some cases, cattle became more than economic assets. For example, in China (Song dynasty onward) and ancient Egypt (along the Nile Valley), where cattle were regarded as family members or partners in agricultural labor, there were taboos against killing them casually for food.

Some herding communities, for instance, the East African Cattle Complex tribes, even developed a profound veneration of cattle based on deep emotional, spiritual, and social bonds with cattle as symbols of identity, wealth, life, and even divinity.

The Importance of Cattle Dung

I’ll leave you with this amazing story of how the dung of grazing cattle restored ecological balance and turned barren desert into a thriving forest.

- With increasing urbanization, keeping cows at home is no longer feasible for many, giving rise to a thriving dairy Industry in India, but the Indian dairy industry is quite unique. More about this in a separate article. ↩︎

- Traditionally, Brahmins were discouraged from bearing arms or engaging in violence. However, one of their primary social roles was to serve as religious and moral advisors, prominently to kings. In other words, they were entrusted with the delicate task of speaking truth to power, even at the risk of angering a ruler trained for battle. Classical texts treat the killing of a Brahmin (brahmahatya) as a sin of the gravest kind, beyond forgiveness or atonement. This severity functioned as a safeguard for Brahmins, protecting them from the consequences of offending powerful rulers. More importantly, it enabled Brahmins to continue speaking truth to power without fear of consequences. ↩︎

Leave a Reply