When it comes to food etiquette, modern Indians seem caught in a strange confusion – a sense of shame for indigenous traditions as viewed through the Western lens, and a fierce defensiveness when those same traditions are critiqued by outsiders.

This is because very few of us today truly understand Indian food-related customs in their original social and cultural contexts. What we preserve are distorted or superficial versions of these customs. If we are genuinely committed to keeping our traditions alive, we must at least seek to understand them in their full depth and authenticity.

In this post, I describe traditional Indian food etiquette mainly based on how I saw my grandparents practice it. Please feel free to add to my article by writing about your own experiences in the comments.

The Serious Business of Eating

In India, eating is not traditionally a casual, social, or communal activity. It is done primarily in the sanctity of the home. Food is prepared from scratch by the women of the household using whole ingredients, first offered to the Gods, and then partaken by the family as a blessing.

In most homes, especially in villages, meals are eaten with the fingers, seated cross‑legged on the floor and bent forward slightly while eating. It is considered an act of humility and respect to the food (anna) to eat this way, acknowledging it as a gift from Mother Earth and the Gods.

Within the traditional Indian household, the roles around food are clearly defined. Cooking and serving are typically the domain of women. Mothers, wives, daughters, and sisters prepare meals and serve family members with devotion.

Men, children, and the elderly are served first, while the women eat later, making do with whatever is left after the rest of the family has been fed. Most women view this as a labor of love and take genuine pleasure and pride in ensuring that their family is nourished and content.

Food as Prasād

In the traditional Indian worldview, food is never just food; it is something obtained through divine favor (prasād). This understanding shapes the way meals are prepared and consumed.

In orthodox Hindu households, food is prepared in a state of purity, in a sanitized kitchen, only after bathing and donning clean clothes. Once the food is prepared, it is first offered to the Gods by placing in front of the family altar with prayers.

Once it has been “accepted” by the Gods, the food is thought to be blessed. It is then eaten by family members.

Etiquette Around Food

My dad’s mother was a deeply orthodox woman who faithfully observed all the practices prescribed in the scriptures. She woke up before dawn every day, hours before the rest of us. By the time we were up, she had already bathed, donned “ritually pure1” clothes, cleaned and sanctified the kitchen, and started on food preparation for the day.

I learned as a very small child not to run recklessly around the house, because if I accidentally bumped into Grandma, I would defile her ritual purity. She would shake her head and go off to bathe and change all over again. Food had to be cooked in a state of ritual purity before she would eat it.

Dad’s mother was especially orthodox and lived an austere, disciplined life. Mum’s parents, while not quite as strict, also observed rules of ritual purity and eating etiquette based on Hindu scriptures.

Only the right hand was used for eating. The left hand was not allowed to touch even the plate you were eating from, let alone the food itself. This was not for the reason most people seem to think.2 The reason you did not touch your food with the left hand was so that you could keep that hand clean for drinking water or serving yourself seconds.

If you wanted a drink of water while eating, you picked up the tumbler to the left of your plate with your left hand, tilted your head back, and poured the water into your mouth without letting the tumbler touch your lips.

The women in the family served the children and the men first. Later, they ate together, serving themselves. Sometimes, the children lingered and helped with serving. If I served someone freshly cooked food like rice or vegetables (using a ladle, of course), I was told to go wash my hands before touching the pickle jar.

As a child, I found these rituals burdensome and pointless. However, there is an underlying logic to them, even if orthodox families do take them to the extreme.

Different Categories of Food

Food is traditionally divided into different categories based on how long each can be preserved.

Pickles, for instance, can be preserved for weeks or even months. You do not want to contaminate them with food that spoils easily, such as rice, lentils, or vegetables, which are cooked fresh and meant to be eaten the same day.

Apart from this, a strict separation is maintained between food that is being eaten and food kept in shared serving containers, as cross-contamination with saliva can spread disease. This is why the right hand is used for eating, while the left hand is reserved for serving yourself.

Eating out of the same plate is not allowed, except between husband and wife. Water, however, can be shared, so long as you do not put your lips to the tumbler or touch it with food-stained fingers.

Leftovers are treated as yet another category. These days, refrigeration makes it easier to store leftovers safely, but traditionally, there were strict rules for storing or eating leftovers.

Most cooked foods spoiled overnight without refrigeration and were, therefore, not stored. They were usually given away to poor people who came by after dinnertime to ask if there were leftovers. If no one came, the food was fed to domestic animals.

Some cooked foods are easier to store overnight than others. For example, you can add water to cooked rice, and it will ferment slightly to become a cooling probiotic food, great for breakfast on a hot summer day. Dry rotis (flatbreads) are also okay to keep overnight. They do go stale, but are still safe to eat and can be made palatable in various ways for breakfast.

Even so, leftovers are not typically offered to elderly or frail people.

All of these are common-sense rules that still apply today, but they were especially important in the past, to protect people against diseases and infections in a hot climate before refrigerators or antibiotics.

Where Do Our Food Traditions Come From?

Food-related rules and etiquette in India have been documented in detail right since ancient times. They have been written about in a vast body of religious, legal, and medical literature, spanning the Vedic corpus, the Dharmasūtras, Smritis, and classical Ayurvedic texts such as the Charaka Saṃhitā and Sushruta Saṃhitā.

While the Vedas lay the spiritual groundwork for viewing food as sacred and life‑sustaining, it is in the Dharmasūtras and Dharmashāstras that we find detailed prescriptions for ritual purity, hygienic food handling, and eating practices in everyday life.

Texts such as the Āpastamba Dharmasūtra, Gautama Dharmasūtra, and Manusmriti discuss which foods are fit or unfit for consumption, and under what conditions foods become ritually impure.

These prescriptions are consistent with Ayurveda’s medical emphasis on digestive balance, hygienic food preparation, and mindful eating. Taken together, they reflect an integrated worldview in which physical, mental, and spiritual purity were closely intertwined.

Why Do Indians Eat with Their Fingers?

For as long as we have attested history in India, going right back to the Vedas, we find descriptions of spoon-like or ladle-like implements used in religious as well as domestic contexts (food preparation, cooking, serving).

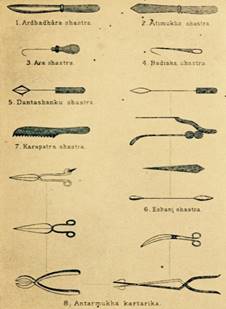

The Sushruta Samhita, an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, describes over 120 surgical implements designed for specific procedures. Many modern surgical instruments and techniques used around the world today have, in fact, been directly influenced by this text.

In other words, ancient Indians were by no means unfamiliar with the manufacture or use of tools and implements. Why, then, did they prefer to eat with their fingers?

Going back to my grandmother, who used a wide array of spoons, ladles, turners, and serving implements in her kitchen – I never once saw her eat directly from a spoon. If you served her food with a spoon, she would use the spoon to scoop, then tilt her head back slightly and let the food drop into her mouth from a short distance.

Visiting the homes of orthodox relatives, I was always fascinated to find that each member of the family had their own steel plate that they recognized, and nobody would eat from anybody else’s plate.

In the Vedas and other ancient texts, certain types of utensils are described as being ritually pure (for example, those made of gold or silver, or disposable utensils made from leaves and discarded after a single use). By implication, most reusable utensils were not considered ritually pure.

This may have been because reusable utensils were traditionally made from porous materials such as clay or wood. Given that modern detergents did not exist, bacterial buildup and contamination over time would have been a real concern, especially in hot and humid climates.

Metal spoons and utensils did exist from very early periods, but they were not widely available to the masses. Hands, by contrast, were always available and could be washed thoroughly before and after eating.

There were other practical advantages to eating with the fingers. Touch allowed one to test for food spoilage (slimy texture), impurities (such as pebbles in cooked rice or bones in fish), and temperature (making sure the food was not too hot) before it reached the mouth.

Ancient Heritage vs. Modern Compulsions

Everywhere in the world, people originally ate with their fingers. Over time, some cultures adopted spoons, forks, knives, and chopsticks as everyday eating implements. Other cultures continued to eat with hands until more recently, shifting to cutlery under external influence only in the last century or so.

India has famously resisted external influence in the matter of food etiquette.

One reason for this is that, in India, food is deeply embedded in religious life, as described above, and food etiquette is therefore practiced according to scriptural norms despite the evolution of material conditions and technology.

Another reason is that, for most of our history, eating was an intensely private affair. It was something you did only in the safety of your home, among family and close friends, without outside eyes to judge or comment.

Of course, as social eating becomes more widespread, a new generation of Indians find themselves struggling to reconcile an ancient tradition they take comfort in with the pressures of fitting into a globalized world shaped largely by Western norms.

Some deal with this by happily abandoning old customs and adopting new ones. Others take pride in holding firmly to traditional ways. Most of us adapt in public spaces while preserving tradition at home.

Personally, sitting on the floor and eating with my fingers off a banana leaf takes me back to my childhood. It is neither a matter of pride nor of embarrassment. It is simply a feeling of being at home and at ease. I feel no need to impose something so personal on those who do not share the cultural context to experience it in the same way.

Why the Lack of Hygiene in Indian Street Food

Street food in India is, sadly, not famous for its hygiene. How does one explain this stark contrast between the way food is handled at home versus outside the home?

In the decades following Independence, rapid urbanization turned Indian cities into magnets for migrant workers, mostly men who arrived by the trainload from rural areas in search of work that might lift their families out of poverty. These men had neither the money nor the time for proper meals at respectable eateries. All they could afford was a quick bite at a cheap roadside stall.

This sudden and massive demand for fast, inexpensive food was met by an explosion of informal, largely unregulated stalls wherever a little space could be found. Speed and affordability became the main priorities; hygiene and quality were often sacrificed in the rush to serve volume at rock-bottom prices.

Another feature of commercial food spaces in India is that they are run predominantly by men. Female cooks and servers are largely absent from public food spaces, in sharp contrast to the domestic sphere, where women oversee food preparation and serving with care and devotion.

Perhaps because of this, eating out was not traditionally considered respectable, as public eateries did not follow the same norms of hygiene and sanitation as the home. Today, of course, street food has become a part of mainstream Indian culture, and there is a gradual improvement in quality and hygiene in response to the expectations of a more discerning customer base.

- Ritual purity is the state of being clean and prepared for worship, which includes the observance of specific ritual actions in addition to physical cleanliness. ↩︎

- “The right hand is for eating; the left is for cleaning up after you go to the toilet.” This explanation, commonly offered in discussions of eating with the fingers, can be traced to Islamic legal norms that developed in Arabia, where a formal distinction was made between the right hand for social and honorable acts and the left for private or polluting ones. In India, where water is abundant and washing is universal, this explanation does not account for the practice of eating with your right hand. The real reason the right hand is used for eating is that it is the skilled hand. For most people, the left is the awkward hand, and they naturally avoid using it for anything that requires care, precision, or respect. ↩︎

Leave a Reply